The Islamic State’s leader died this month. What type of leader might come next?

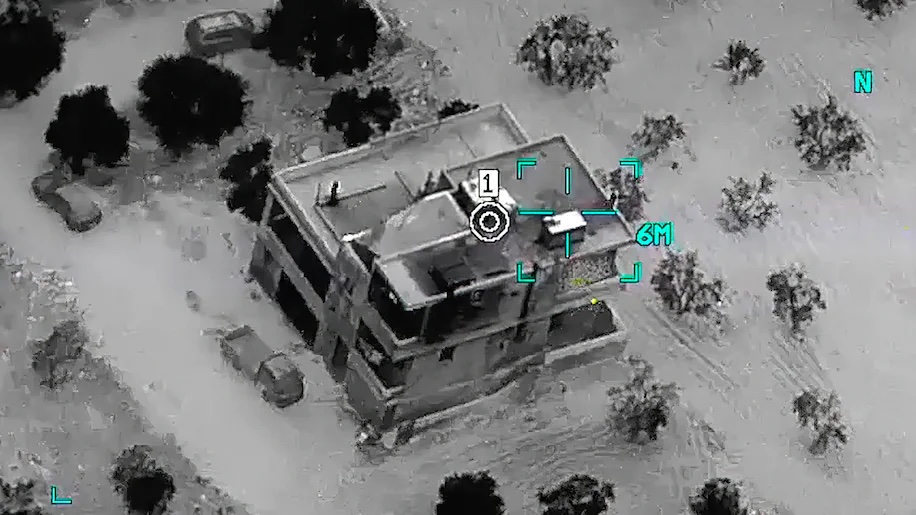

This month, a U.S. Special Forces mission targeted Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi, the leader of the Islamic State. Al-Qurayshi reportedly detonated explosives during the raid, killing himself and members of his family.

His death follows previous U.S. raids that killed al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, al-Qaeda in Iraq leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. But what type of leader was al-Qurayshi — and what type of leader might succeed him?

The Islamic State leader was a relative unknown

Our research explains why these questions are critical when trying to gauge the impact on a terrorist group after its leader has died. Our forthcoming book studying terrorist leadership types, “Terror in Transition: Leadership and Succession in Terrorist Organizations,” suggests that al-Qurayshi meets the criteria of a “figurehead,” a silent type of leader who did not actively lead the Islamic State.

Al-Qurayshi became leader of the Islamic State in 2019 as a relative unknown. He operated in hiding, apparently out of fear of the kind of counterterrorism action that killed al-Baghdadi, his predecessor.

The open-source information to date suggests al-Qurayshi did not drive his organization’s tactics, its ways of gathering resources or its mission. He was largely an absentee leader who relied on others to steer the group.

This type of leader, our research found, is not well-positioned to rejuvenate a struggling organization, like the group al-Qurayshi inherited — but al-Qurayshi’s death now may create an opening for a more hands-on successor. Thus, while his death may have dealt a serious blow to the Islamic State, as U.S. officials claim, a more dynamic leader may soon emerge to fill this gap.

We identified 5 types of leaders

To develop our typology of leaders, we examined 33 religious-linked terrorist organizations that experienced at least one leadership change. We identified five types of leaders, based not on personality traits, but the direction a leader takes the organization compared to the foundation laid by founding leaders. Do successors undertake change or continuity? Are they actively involved in determining the group’s next steps?

One of the most common types, what we call “the caretaker,” maintains the path set by the group’s founder and does not make significant changes. Al-Qaeda’s current leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, is one example: Since 2011, he has maintained the legacy of bin Laden.

Another common type, “the fixer,” is a leader who makes significant adjustments to a group’s tactics or the way it acquires and manages resources. Interestingly, as the leader of Egyptian Islamic Jihad in the 1990s, Zawahiri operated in fixer mode after taking over from a figurehead leader, suggesting that an individual can pursue different types of leadership.

A third type of leader, “a visionary,” is someone who makes major changes to their group’s tactics and its mission. This type of leader may have the most potential to rejuvenate a fledgling organization by infusing it with both new framing and tactics, but may also introduce cleavages. Al-Qurayshi’s predecessor, al-Baghdadi, was this type of leader. He declared the creation of a new caliphate, naming himself as chief religious and political leader, and transitioned the organization into a pseudo-government.

A fourth and less common type of leader, “a signaler,” makes significant changes to the group’s mission but leaves its tactics and resource acquisition approach largely unchanged. The previous iteration of the Islamic State, the Islamic State of Iraq, had this type of leader in both Abu Hamza al-Muhajer and Abu Umar al-Baghdadi. They transitioned the group from al-Qaeda in Iraq to the Islamic State of Iraq, a change in how the group presented its mission, though it did not yet function as the state it declared itself to be.

What do we know about ‘figureheads’?

Figureheads like al-Qurayshi are quite rare, our study found. Most leaders of religious terrorist organizations play a more active role managing tactics, resources, and/or the mission. Admittedly, analysts know little about him compared with other leaders — so why do we categorize al-Qurayshi as a figurehead? For one, the group moved to de-emphasize the importance of its leader even before Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s death, so Qurayshi inherited a group with less emphasis on his role.

Given his religious training and experience as an Islamic State judge supervising its courts, it’s interesting that Qurayshi didn’t take a more prominent role in determining the Islamic State’s direction. He was the only Islamic State leader not to issue a video or voice address, for instance. This lack of communication with his followers meant that he could not play a significant role in shaping the group’s mission or ideology.

Islamic State detainees described him as a “ghost,” claiming that they did not even know what he looked like. His limited influence may have also been a result of his struggle to establish credibility, both because of speculation that he lacked the necessary qualifications to be caliph — and because of revelations that he had snitched on his associates while detained by U.S. forces in 2008.

In addition, the Islamic State grew more decentralized after the collapse of the caliphate in 2017 under al-Baghdadi’s leadership. Decentralization can help an organization withstand counterterrorism pressure but also hinders a leader’s ability to direct attacks. The Islamic State had already returned to its insurgency roots before Qurayshi took over, so he may have not seen a need to manage operations, especially when increased involvement would come with greater risks to his life.

What comes next?

In other examples of a figurehead’s death, rare as they are, these deaths paved the way for the emergence of more dynamic leaders. The Islamic State has a robust history of such leaders through its evolution from al-Qaeda in Iraq to the Islamic State of Iraq to the current Islamic State. The big question now is whether the death of Qurayshi may mean a more dynamic leader is poised to emerge, particularly as the Islamic State is trying to gain momentum across Syria and Iraq.

Tricia Bacon is a member of ASMEA and an associate professor in the School of Public Affairs at American University. Elizabeth Grimm is an associate professor of teaching in the Security Studies Program in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

The opinions expressed here are their own.

Read the original post on The Washington Post.

Photo Credit: (Defense Department/AP)